The

Japanese tradition of taking care of one's own in old age is fast

headed towards extinction. The cause, as for so many of Japan's current

and future woes, is down to demographics. Using statistics kindly

provided by Professor Noriko Tsuya of the Department of Economics at

Keio University, Beacon Reports paints a grim picture of what we, as

residents of Japan, will most likely experience firsthand. Professor

Tsuya serves as chair of the subcommittee on population change and

economy for The Science Council of Japan. She also chairs the

subcommittee on population and social statistics for the statistics

committee of the Cabinet Office and chairs the committee on population

projection for the Social Security commission of the Ministry of Health,

Labor, and Welfare.

In many Asian cultures, including that of Japan, it is tradition for the eldest son to look after aging parents. That burden, of course, falls largely on the spouse of the eldest son. Therefore, as a group, women have been de facto primary care givers to the elderly in Japanese society. Will there be enough of them to continue this time-honored tradition given Japan's changing demography?

We all know the headline demographics — Japan's rapid aging and low birth rate means the population will shrink by one-third, down on average by about one million people per annum over the coming decades. The ratio of those of working age (aged 15 - 64) to the elderly (seniors, aged 65+) will shrink from roughly 3:1 to 1:1 so that only about half the population will be in paid employment by 2060, when those aged 65+ will represent 40% of the total population.

Figures for 2010 show about 11% of Japan's total population is aged 75+. For every 100 persons aged 75+, there are 117 primary care givers (Japanese women aged 40 - 59). And only 3% of Japan's total population is aged 85+.

At first glance, then, it would appear that the supply of and demand for informal care is in balance — the ratio of care is almost 1:1 for those aged 75+. But that's not quite the case, as on average 72.3% of women aged 40 - 59 hold jobs outside the home. The burden of holding two jobs, one formal and another informal, puts an added strain on care givers.

While currently stressed, the tradition of informal care giving could survive if not for rapidly changing demographics.

Sixty years ago, life expectancy at birth averaged 61.3 years (59.6 for males and 63 years for females). With better sanitation, healthcare and increased living standards, those today aged 65 can look forward to an average 21.4 additional years of life (18.9 for males and 23.9 for females).

Yet the fertility rate has fallen steadily since 1947. The number of average births per woman in Japan is currently 1.4, well below America's 1.9 and well below the replacement level fertility rate of 2.1, the level of fertility at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next.

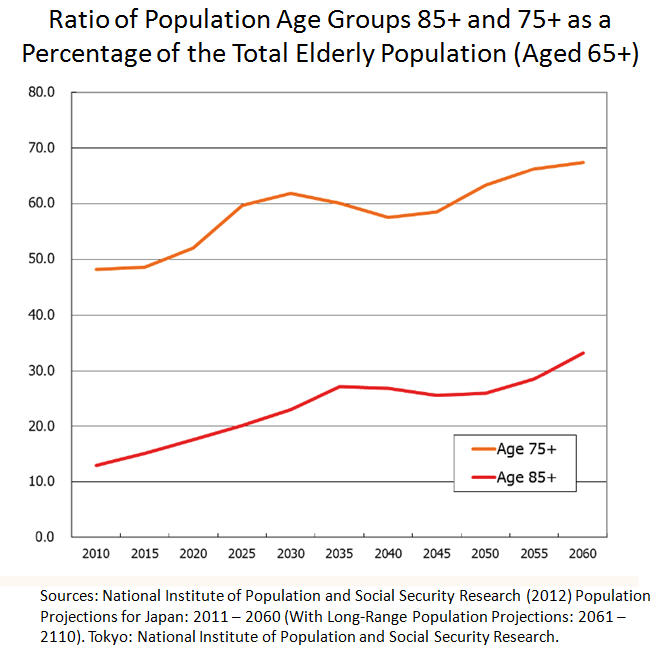

Simply put, the society is aging. As a result, the percentage of the population aged 75+ is expected to increase from 11% to 20% by 2035. Likewise, the percentage of the population aged 85+ is expected to increase from 3% to 9% over that same period.

By 2060, 27% of Japan's total population will be aged 75+, with more than 13% aged 85+.

The fact is, those aged 85 - 89 are in the most rapidly growing age segment of Japanese society. That's important, because it is generally accepted that, as a group, health declines rapidly after age 85. By 2060, one-third of all seniors will be aged 85+ and by 2015 (very soon) more than 50% of all seniors will be aged 75+.

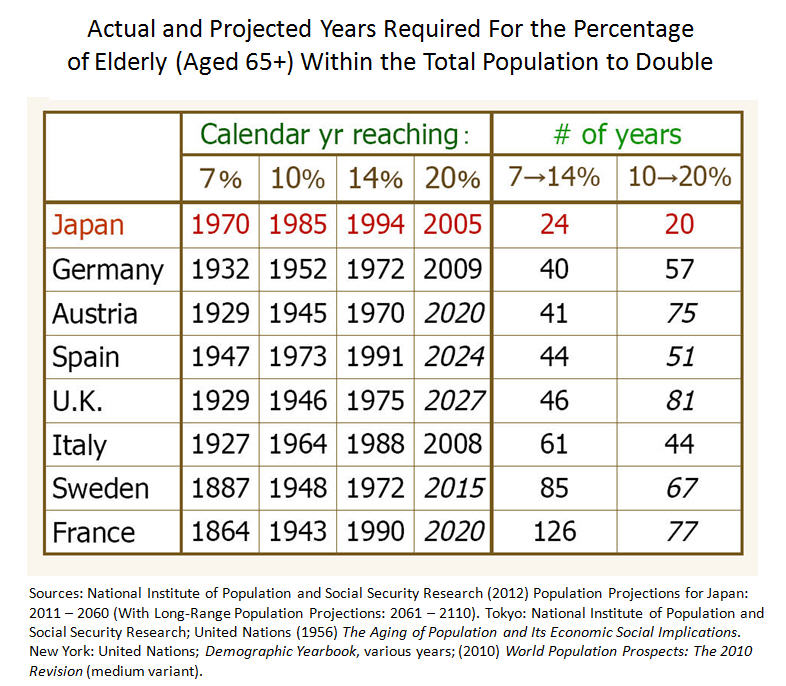

The speed of change is

frightening and difficult to comprehend. As the below chart shows,

Japan's population is aging faster than any other developed nation.

France's elderly (aged 65+) doubled in size from 7% to 14% of the total

population over the course of 126 years; Japan took 24 years to achieve

the same doubling. France's elderly are expected to double in size from

10% to 20% of the total population over a 77 year period for the year

ending in 2020; Japan had already accomplished that feat over a 20 year

period for the year ended 2005.

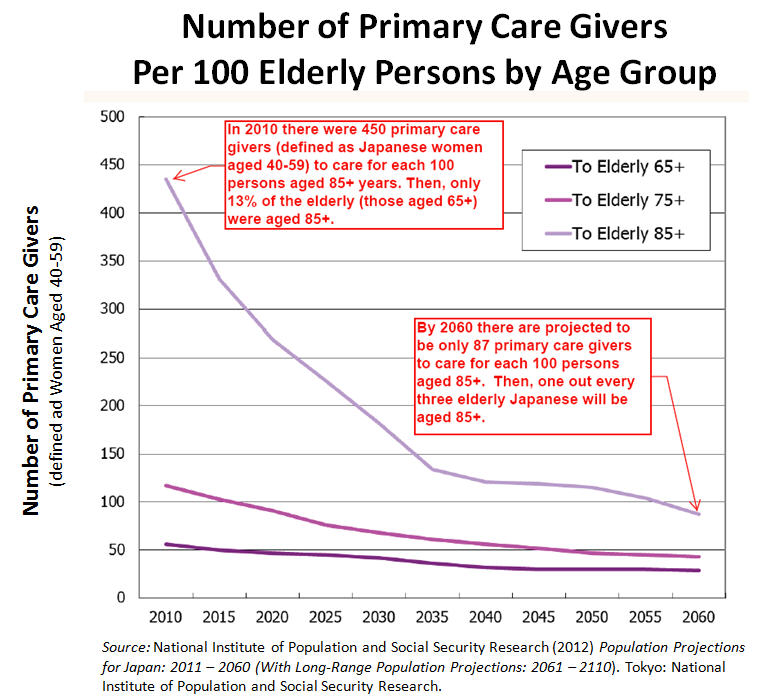

The impact of rapid demographic changes on the tradition of primary care giving will be devastating. This graph shows the number of primary care givers per 100 elderly as broken out by age group.

In 2010 there were 117 and 435 primary care givers, respectively, for every 100 elderly aged 75+ and 85+.

Roll the calendar forward to the year 2035 and the story darkens. In 2035 there are projected to be, respectively, only 61 and 134 primary care givers for every 100 persons aged 75+ and 85+.

Roll the calendar forward even further to 2060 and there will be, respectively, 43 and 87 primary care givers for every 100 persons aged 75+ and 85+.

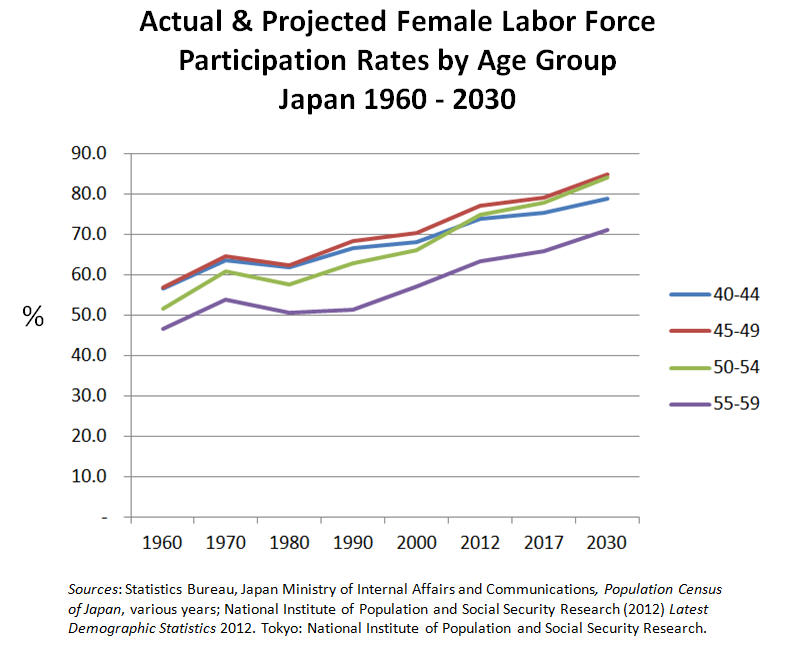

To add to the troubles, the historic trend of increasing female employment is expected to continue. This chart shows between 2012 - 2030 another 7.4% of primary care givers will likely join the workforce, taking the average women aged 40-59 in paid employment to almost 80%.

Care workers will

therefore be far outnumbered and overworked. Beacon Reports asks, who

will take care of the elderly? By 2060, perhaps much earlier, the

tradition of primary care giving will be a fading memory.

Professor

Noriko Tsuya of the Department of Economics at Keio University. The

projections presented in this report are based on the most likely

expected outcomes. The statistical degree of error increases with the

length of projection. Short term projections are likely to be more

accurate than those that are longer in term. All opinions, based the

statistics provided by Professor Tsuya, are that of Beacon Reports

alone.

In many Asian cultures, including that of Japan, it is tradition for the eldest son to look after aging parents. That burden, of course, falls largely on the spouse of the eldest son. Therefore, as a group, women have been de facto primary care givers to the elderly in Japanese society. Will there be enough of them to continue this time-honored tradition given Japan's changing demography?

We all know the headline demographics — Japan's rapid aging and low birth rate means the population will shrink by one-third, down on average by about one million people per annum over the coming decades. The ratio of those of working age (aged 15 - 64) to the elderly (seniors, aged 65+) will shrink from roughly 3:1 to 1:1 so that only about half the population will be in paid employment by 2060, when those aged 65+ will represent 40% of the total population.

Figures for 2010 show about 11% of Japan's total population is aged 75+. For every 100 persons aged 75+, there are 117 primary care givers (Japanese women aged 40 - 59). And only 3% of Japan's total population is aged 85+.

At first glance, then, it would appear that the supply of and demand for informal care is in balance — the ratio of care is almost 1:1 for those aged 75+. But that's not quite the case, as on average 72.3% of women aged 40 - 59 hold jobs outside the home. The burden of holding two jobs, one formal and another informal, puts an added strain on care givers.

While currently stressed, the tradition of informal care giving could survive if not for rapidly changing demographics.

Sixty years ago, life expectancy at birth averaged 61.3 years (59.6 for males and 63 years for females). With better sanitation, healthcare and increased living standards, those today aged 65 can look forward to an average 21.4 additional years of life (18.9 for males and 23.9 for females).

Yet the fertility rate has fallen steadily since 1947. The number of average births per woman in Japan is currently 1.4, well below America's 1.9 and well below the replacement level fertility rate of 2.1, the level of fertility at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next.

Simply put, the society is aging. As a result, the percentage of the population aged 75+ is expected to increase from 11% to 20% by 2035. Likewise, the percentage of the population aged 85+ is expected to increase from 3% to 9% over that same period.

By 2060, 27% of Japan's total population will be aged 75+, with more than 13% aged 85+.

The fact is, those aged 85 - 89 are in the most rapidly growing age segment of Japanese society. That's important, because it is generally accepted that, as a group, health declines rapidly after age 85. By 2060, one-third of all seniors will be aged 85+ and by 2015 (very soon) more than 50% of all seniors will be aged 75+.

|

|

The impact of rapid demographic changes on the tradition of primary care giving will be devastating. This graph shows the number of primary care givers per 100 elderly as broken out by age group.

|

In 2010 there were 117 and 435 primary care givers, respectively, for every 100 elderly aged 75+ and 85+.

Roll the calendar forward to the year 2035 and the story darkens. In 2035 there are projected to be, respectively, only 61 and 134 primary care givers for every 100 persons aged 75+ and 85+.

Roll the calendar forward even further to 2060 and there will be, respectively, 43 and 87 primary care givers for every 100 persons aged 75+ and 85+.

To add to the troubles, the historic trend of increasing female employment is expected to continue. This chart shows between 2012 - 2030 another 7.4% of primary care givers will likely join the workforce, taking the average women aged 40-59 in paid employment to almost 80%.

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment