Many economists believe that Japan will become a net debtor nation. Analysts differ about when. Earlier this year we reported that Jesper Koll, managing director of research at JPMorgan Securities Japan, said, "The time is now... It’s here. It’s 'Sayonara Japan' as a net creditor country." Richard Katz believes that point is years away -- he's not even sure it is going to happen or if it does, that it will cause capital flight as has happened in Greece. Katz is editor-in-chief of the Oriental Economist Report. He is a distinguished lecturer, a former adjunct professor, and an economist who has written about Japan and US relations for three decades. Joining us to explain his latest thinking, is Katz -

Solomon: Why is Japan not going to become the next Greece?

Katz: The point at which Japan is in danger of capital flight, like Greece, is when Japan's current account becomes chronically in deficit. Some people say that could be five or ten years from now. I think it will be later -- I'm not even sure it's going to happen. Japan will most likely become a chronic trade deficit country within this decade, but the current account is different. The current account is the sum of Japan's trade balance plus the income earned on Japan's overseas assets (profits of overseas subsidiaries as well as stocks and bonds held outside Japan). Japan is not vulnerable now because it runs a big current account surplus. Even though the trade balance has been in deficit so far this year, the current account is still in surplus and will remain so for some time to come. If and when Japan does turn into a chronic deficit country, that would be a game-changer which would gradually raise the now-tiny risk of a Greek type crisis. But it would not spark an immediate crisis because Japan has a cushion of $3.3 trillion in net overseas assets.

Solomon: Why is the current account so crucial?

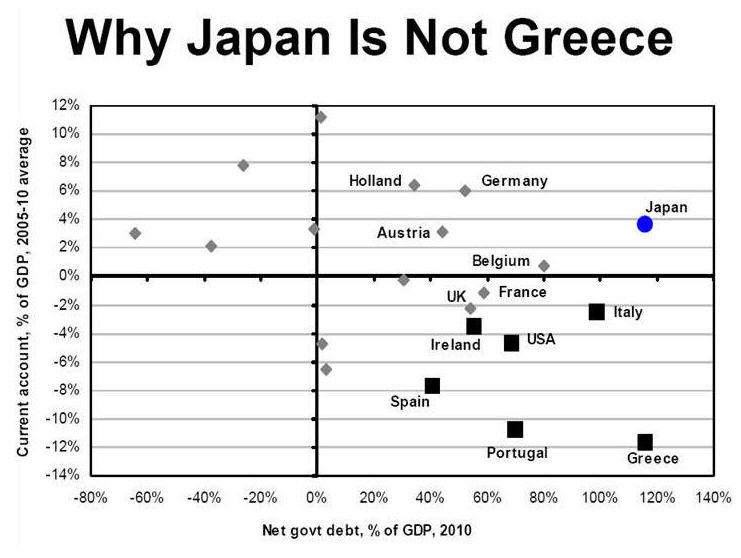

Katz: Running a current account deficit means that you are borrowing money from foreigners, who can easily withdraw it. All of the Euro-crisis countries had not only big government debts, but also big chronic current account deficits. Other European countries with government debts just as big, but without big current account deficits, did not go into crisis. To see this, take a look at the four quadrants of this chart. On the horizontal axis is net government debt as a percentage of GDP. The vertical axis is the current account as a percentage of GDP and presented as averages for the period from 2005 to 2010. Every one of the crisis countries -- Greece, Portugal, Spain and Ireland -- are in the right hand lower quadrant represented by the big boxes. The countries that were borrowing huge amounts of money from abroad got into trouble when the Lehman shock sent their deficits way up. They were vulnerable to capital flight; foreigners started taking their money away.

|

Yet not a single country in the upper right-hand quadrant has gone into crisis. These countries have a current account surplus, which means they can finance their debt by themselves. They're not vulnerable to capital flight. Not even all the countries in the lower-right hand quadrant have gone into crisis -- not the UK, not France, nor the US.

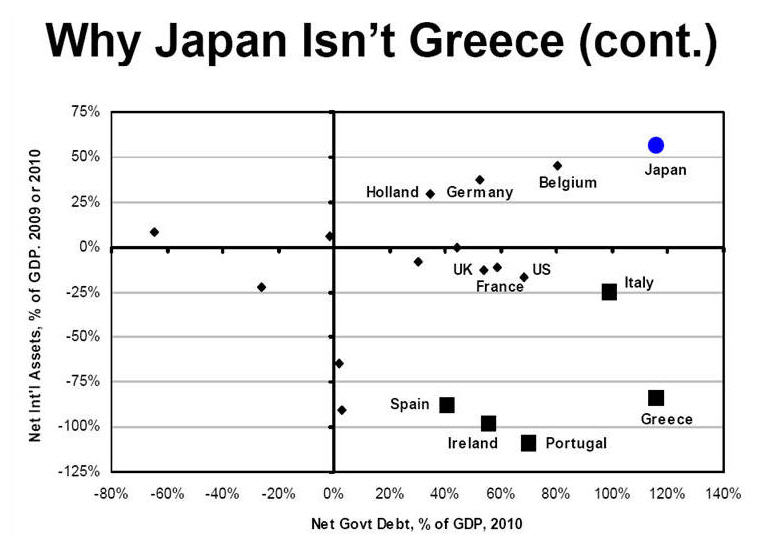

Even when Japan runs a current account deficit, that will not immediately make it vulnerable because it has a big cushion of built-up foreign assets. Here's the same chart, but replacing the current account as a percentage of GDP on the vertical axis with Japan's net international assets.

Even when Japan runs a current account deficit, that will not immediately make it vulnerable because it has a big cushion of built-up foreign assets. Here's the same chart, but replacing the current account as a percentage of GDP on the vertical axis with Japan's net international assets.

|

Again, crisis countries are in the lower right-hand quadrant. They owe a lot of money because they've been borrowing for many years. Yet all the countries in the upper right have been running surpluses for many years. They have built up a cushion of assets.

When a country has both internal and external imbalances, that's when you have a crisis. A domestic crisis alone is manageable. That's why Japan isn't Greece.

Solomon: How would that cushion work in practice?

Katz: Suppose Japan were running a current account deficit and, for some reason, foreigners became reluctant to lend to Japan. In that case, Japan could easily sell some of their international assets. At the end of 2011, the Ministry of Finance’s foreign exchange reserves amounted to $1.29 trillion. At today’s exchange rate, that is equal to 20% of GDP. In addition, net private overseas assets at the end of October 2011 amounted to $2 trillion (¥155 trillion). That equals another 33% of GDP. About 60% of those private assets are liquid financial assets, such as stocks, bonds and bank loans. That foreign investors can see this cushion is yet another reason they are unlikely to bet against Japan’s creditworthiness for years to come, just as deposit insurance reduces the chance of a run on the banks.

Solomon: Why would private parties that own foreign assets feel pressured to sell them? They're not under the control of the Japanese government.

Katz: If Japan were having a capital flight crisis that raised interest rates at home, it would pay private investors to shift some of their overseas bond and stock investments back to Japan to take advantage of those higher rates. Also, if Japan is running a big current account deficit, that means that private parties in Japan are building up debts to foreigners that they must pay in foreign hard currencies -- mostly in dollars. They need to get these dollars from somewhere. Japanese overseas assets are one source.

Solomon: Would not the government's sale of $1.29 trillion in foreign reserves simply increase the budget deficit? The ratings agencies and bond vigilantes, I think, would take notice.

Katz: They have no impact on the budget deficit, but do have an impact on the balance of payments and on the government’s cumulative balance of international assets and liabilities. That is a flow issue vs. stock issue. Rating agencies actions do not seem to have had much impact on market rates of government notes and bonds. Total overseas assets amounting to 55% of GDP, 20% owned outright by the government, should be enough to deal with bond market vigilantes.

Solomon: Can you explain why it doesn’t affect the budget deficit?

Katz: Today, Japan is running a current account surplus. Its net stock of private and government-owned foreign assets is increasing. If the current account turned negative, those assets would decrease. In this scenario, the government and private entities are not issuing new bonds to finance the current account deficit; they are selling existing assets, just as if they had sold a bridge to pay down debt. The net international assets of Japan as a whole would decline. But this action would no more increase the government budget deficit, than the Ministry of Finance increasing its reserve assets lowers the budget deficit today. The balance of payment and budget deficit issues in this case are separate issues, because Japan does not have to issue new debt to finance a current account deficit.

Solomon: Earlier this year I asked J. Koll to comment on the notion Japan had a huge cushion of overseas assets on which it could rely to finance its trade deficit. He said, "The income account is not huge. It is only 2% of GDP, almost nothing..... As anyone who has ever tried it, living off your assets is a very difficult thing to do." How do you respond?

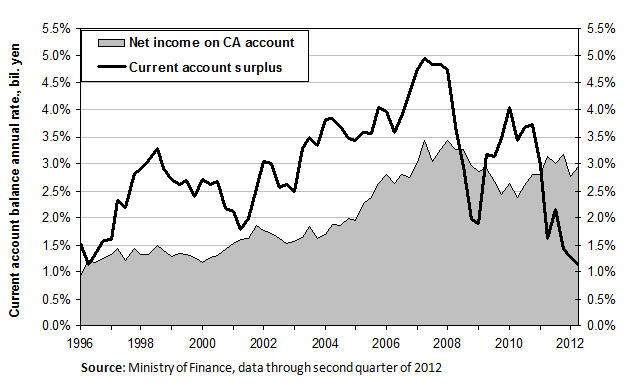

Katz: The income account is about 3% of GDP, not 2% as you can see by the gray area in this chart.

When a country has both internal and external imbalances, that's when you have a crisis. A domestic crisis alone is manageable. That's why Japan isn't Greece.

Solomon: How would that cushion work in practice?

Katz: Suppose Japan were running a current account deficit and, for some reason, foreigners became reluctant to lend to Japan. In that case, Japan could easily sell some of their international assets. At the end of 2011, the Ministry of Finance’s foreign exchange reserves amounted to $1.29 trillion. At today’s exchange rate, that is equal to 20% of GDP. In addition, net private overseas assets at the end of October 2011 amounted to $2 trillion (¥155 trillion). That equals another 33% of GDP. About 60% of those private assets are liquid financial assets, such as stocks, bonds and bank loans. That foreign investors can see this cushion is yet another reason they are unlikely to bet against Japan’s creditworthiness for years to come, just as deposit insurance reduces the chance of a run on the banks.

Solomon: Why would private parties that own foreign assets feel pressured to sell them? They're not under the control of the Japanese government.

Katz: If Japan were having a capital flight crisis that raised interest rates at home, it would pay private investors to shift some of their overseas bond and stock investments back to Japan to take advantage of those higher rates. Also, if Japan is running a big current account deficit, that means that private parties in Japan are building up debts to foreigners that they must pay in foreign hard currencies -- mostly in dollars. They need to get these dollars from somewhere. Japanese overseas assets are one source.

Solomon: Would not the government's sale of $1.29 trillion in foreign reserves simply increase the budget deficit? The ratings agencies and bond vigilantes, I think, would take notice.

Katz: They have no impact on the budget deficit, but do have an impact on the balance of payments and on the government’s cumulative balance of international assets and liabilities. That is a flow issue vs. stock issue. Rating agencies actions do not seem to have had much impact on market rates of government notes and bonds. Total overseas assets amounting to 55% of GDP, 20% owned outright by the government, should be enough to deal with bond market vigilantes.

Solomon: Can you explain why it doesn’t affect the budget deficit?

Katz: Today, Japan is running a current account surplus. Its net stock of private and government-owned foreign assets is increasing. If the current account turned negative, those assets would decrease. In this scenario, the government and private entities are not issuing new bonds to finance the current account deficit; they are selling existing assets, just as if they had sold a bridge to pay down debt. The net international assets of Japan as a whole would decline. But this action would no more increase the government budget deficit, than the Ministry of Finance increasing its reserve assets lowers the budget deficit today. The balance of payment and budget deficit issues in this case are separate issues, because Japan does not have to issue new debt to finance a current account deficit.

Solomon: Earlier this year I asked J. Koll to comment on the notion Japan had a huge cushion of overseas assets on which it could rely to finance its trade deficit. He said, "The income account is not huge. It is only 2% of GDP, almost nothing..... As anyone who has ever tried it, living off your assets is a very difficult thing to do." How do you respond?

Katz: The income account is about 3% of GDP, not 2% as you can see by the gray area in this chart.

|

The goods and services trade deficit expanded to 1.5% of GDP in the first half of 2012. It would have to double to wipe out income surplus and end the current account surplus. The trade deficit would have to triple to bring the current account to a deficit of about 1.5%. While I was wrong in expecting the trade surplus to return this year, it remains to be seen how that will go in the coming years. I still think Japan is heading to toward a chronic trade deficit, but its size is uncertain. I thought six months ago that this would occur in the 2015 to 2020 period. It may come forward a bit because of the combination of the nuclear shutdown and the ongoing troubles in Europe. A lot depends on the price of fossil fuels, which no one has been good at predicting in periods of economic uncertainty. It depends, for example, on demand from Europe and China, which is uncertain. It also depends on expansion of oil and natural gas production in the US. The upshot is the picture for the current account balance is uncertain, but I think the likelihood of Japan turning to chronic current account deficit by 2015 is very low. It will be driven by the trade situation, and the domestic investment-savings balance will adjust to that.

Solomon: Is the critical factor for Japan’s trade surplus its exports to China and Asia?

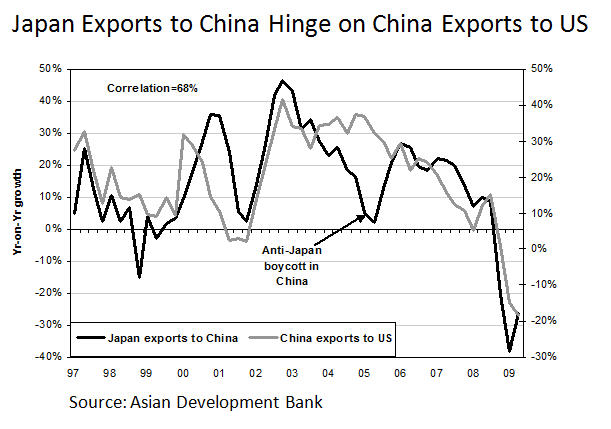

Katz: Japan’s exports to China and the rest of Asia hinge on China/Asia’s own exports to the US and Europe.

|

Most of Japan’s exports to Asia serve as capital or parts inputs for these countries’ own exports. It is the sluggish recovery in the US and the travails in EU that count the most for Japan’s exports. It is the nuclear shutdown and price of fossil fuels that count the most for imports.

Solomon: What does all of this mean of policy going forward?

Katz: The good news is there is no urgency to raise taxes when the global economy is still weak and uncertain. The consumption tax hike passed by the Diet should be delayed until Japan is in better economic health. Second, Japan has the breathing room to apply structural reform to improve long-term growth while being able to use fiscal stimulus as the anesthesia to make the pain of structural reform bearable. Fiscal stimulus need not mean bridges to nowhere. It could be a combination of temporary consumer-oriented tax cuts and public works that help the economy. For example, linking suburban and semi-rural homes to sewage lines and gas pipelines -- homes now served by septic tanks and propane gas tanks -- would greatly reduce air and water pollution while cutting Japan’s energy needs. That would eliminate the need for trucks to service the septic tanks and propane tanks.

Solomon: What does all of this mean of policy going forward?

Katz: The good news is there is no urgency to raise taxes when the global economy is still weak and uncertain. The consumption tax hike passed by the Diet should be delayed until Japan is in better economic health. Second, Japan has the breathing room to apply structural reform to improve long-term growth while being able to use fiscal stimulus as the anesthesia to make the pain of structural reform bearable. Fiscal stimulus need not mean bridges to nowhere. It could be a combination of temporary consumer-oriented tax cuts and public works that help the economy. For example, linking suburban and semi-rural homes to sewage lines and gas pipelines -- homes now served by septic tanks and propane gas tanks -- would greatly reduce air and water pollution while cutting Japan’s energy needs. That would eliminate the need for trucks to service the septic tanks and propane tanks.

Richard Katz is editor-in-chief of The Oriental Economist Report. Katz has written about Japan and US relations for over three decades. He was a visiting lecturer in economics at the State University of New York in Stony Brook and an adjunct professor of economics at New York University Stern School of Business. He's authored two books about Japan -- "Japan, the System That Soured: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Economic Miracle" and "Japanese Phoenix: The Long Road to Economic Revival". In “A Nordic Mirror”, he explained why Scandinavia has recovered from similar structural defects far more quickly than Japan. Richard holds a BA in history from Columbia University (1973) and holds a masters degree in economics from NYU (1996). www.orientaleconomist.com

No comments:

Post a Comment