Summary

The past two years have seen Japan through an unusually volatile business

cycle. The economy posted an unprecedented steep decline in economic

activity in 2009 of 5.2%, only to come roaring back to life in the first quarter of

2010 with an economic growth rate of 4.2%. The bounce was largely credited

to an increase in external demand as well as positive effects of government

stimulus spending. The Tankan Survey conducted by the Bank of Japan

corresponded with the economic improvement, showing five consecutive

quarterly upticks in its index. But this economic bounce will be followed by a

plateau of milder growth in 2011 due to the expected end of the stimulus

effect. Further uncertainties for the economy include an elevated level of

unemployment as well as the export-related impact of the yen’s appreciation

against major currencies.

This quarterly review of Japan’s property markets begins with the ‘Second

Quarter Market Outlook 2010’. This section explains the latest fundamentals

of each property sector and illustrates trends affecting the finance market,

transaction volumes, cap rates, returns and leasing markets. It also provides

a short-term outlook for each of the major property sectors. Over the past six

months, credit conditions in Japan have gradually improved. Cap rates in

prime locations like the Tokyo CBD have stabilised, if not compressed. More

commercial properties traded in Tokyo in the first quarter of 2010 than any

other city worldwide. Interest in the market, however, has been driven more

by wide yield spreads (among the highest of major global markets) than by

strong property fundamentals. Office leasing remains stagnant and the

vacancy rate continues to rise. Retail indicators appear more hopeful in the

near term, with consumer confidence improving and high street rents

beginning to pick up.

The ‘Research Topic’ section provides each quarter a brief analysis of a topic

that is timely and relevant to Japanese real estate markets. In the previous

edition, we pointed out that based on modern portfolio theory Japanese

pensions in general should increase real estate allocations in their portfolios

in order to maximise their potential across the risk-return spectrum. In this

edition, we add a new component to that discussion. We present an

overview of Japan’s capital market and contrast its structure and key players

with Japan’s global peers. The scale of the country’s capital market is

massive. It ranks second only to the US in overall size, and Japan’s

Government Pension Investment Fund, or GPIF, is the largest of its kind in

the world. As we show in our analysis, Japan’s investors—both households

and institutions—deploy their assets in exceedingly risk-averse ways and this

has historically limited the potential for long-term returns. Compared to

global peers, we find that the long-term returns of Japan’s institutional

investors fall short of their overall potential.

2010 Market Outlook

Macro Economy

After posting an unprecedented steep decline in economic activity in 2009

with a contraction of 5.2%, the growth rate in Japan turned positive, rising

4.2% in the first quarter of 2010, thanks to the increase in external demand

and positive effects from the government’s stimulus package. Deutsche Bank

economists expect healthy 3.5% growth in GDP in 2010 to be followed by a

milder plateau of economic growth in 2011, due to the expected end of the

stimulus effect and further uncertainties for the economy given a still high

level of unemployment. The yen’s appreciation against major currencies is

also a big concern for the export-led economy.

The Tankan Survey conducted by the Bank of Japan corresponds with the

current improvement in the economy. The diffusion index (DI) of business

conditions for all industries rose across five consecutive quarters for the

period ending in June 2010. This represents a 9-point gain over the previous

quarter, and a 31-point improvement from the economic trough 15 months

ago. The index for large companies continued to post a robust recovery due

to increases in exports.

current improvement in the economy. The diffusion index (DI) of business

conditions for all industries rose across five consecutive quarters for the

period ending in June 2010. This represents a 9-point gain over the previous

quarter, and a 31-point improvement from the economic trough 15 months

ago. The index for large companies continued to post a robust recovery due

to increases in exports.

Capital Market and Pricing

Previously tight credit conditions are gradually easing. The aggregate amount

of bank borrowings in the real estate industry in Japan was JPY60.4 trillion in

the first quarter of 2010, relatively unchanged from the previous quarter. New

lending for real estate increased 7.6% in the quarter from the same period in

the previous year, and it is the first increase in eight quarters according to the

Bank of Japan. The new finance diffusion index (DI) for J-REITs (red in

Exhibit 4) is still negative in the period, but it has been making continuous

improvement for four quarters running.

Previously tight credit conditions are gradually easing. The aggregate amount

of bank borrowings in the real estate industry in Japan was JPY60.4 trillion in

the first quarter of 2010, relatively unchanged from the previous quarter. New

lending for real estate increased 7.6% in the quarter from the same period in

the previous year, and it is the first increase in eight quarters according to the

Bank of Japan. The new finance diffusion index (DI) for J-REITs (red in

Exhibit 4) is still negative in the period, but it has been making continuous

improvement for four quarters running.

The number of real estate transactions started to increase gradually in the

fourth quarter of 2009, fuelled by a series of successful public offerings by JREITs

as they started to acquire real estate assets. The volume of real estate

assets transacted in Japan in 2010 YTD amounted to JPY1.2 trillion by June

2010, compared to JPY 1.7 trillion in FY2009.

fourth quarter of 2009, fuelled by a series of successful public offerings by JREITs

as they started to acquire real estate assets. The volume of real estate

assets transacted in Japan in 2010 YTD amounted to JPY1.2 trillion by June

2010, compared to JPY 1.7 trillion in FY2009.

Below is the list of selected real estate transactions either completed or

announced in the second quarter 2010. J-REITs dominated major

acquisitions in the first quarter but foreign investors and managers (yellow in

Exhibit 8) became more active in the second quarter, especially Asian

investors, although the sizes of some transactions were small. This is

believed to be because asset prices in Hong Kong and other major Asian

countries rose sharply in 2009, and real estate prices in Japan became

relatively cheap (see also Exhibit 5). During the period, the US-based

Fortress Investment Group acquired JPY20.5 billion in daVinci Holdings debt

owned by BNP Paribas, as well as the subscription rights to new shares,

leaving Fortress the de facto owner of Japan-based daVinci.

announced in the second quarter 2010. J-REITs dominated major

acquisitions in the first quarter but foreign investors and managers (yellow in

Exhibit 8) became more active in the second quarter, especially Asian

investors, although the sizes of some transactions were small. This is

believed to be because asset prices in Hong Kong and other major Asian

countries rose sharply in 2009, and real estate prices in Japan became

relatively cheap (see also Exhibit 5). During the period, the US-based

Fortress Investment Group acquired JPY20.5 billion in daVinci Holdings debt

owned by BNP Paribas, as well as the subscription rights to new shares,

leaving Fortress the de facto owner of Japan-based daVinci.

Market Fundamentals: Office

The leasing market tends to lag behind the economic recovery. In fact signs

of recovery for office fundamentals are not evident yet in Japan. The average

office vacancy rate in Central Tokyo3 has been rising for 30 consecutive

months, and it went up to 9.1% in June 2010, breaking all-time worst records

for five consecutive months.

The vacancy rate for newly developed buildings4 in Tokyo (blue in Exhibit 10)

has now jumped to 40%. In the Shinjuku submarket, the vacancy rate for

newly developed buildings skyrocketed to 89% in June 2010. Historically, the

vacancy rate for overall buildings has lagged the vacancy trend for newly

completed buildings. Based on this leading indicator, therefore, the overall

office vacancy in Tokyo is expected to increase a little further, to be followed

by a slow and gradual recovery starting in late 2010.

The leasing market tends to lag behind the economic recovery. In fact signs

of recovery for office fundamentals are not evident yet in Japan. The average

office vacancy rate in Central Tokyo3 has been rising for 30 consecutive

months, and it went up to 9.1% in June 2010, breaking all-time worst records

for five consecutive months.

The vacancy rate for newly developed buildings4 in Tokyo (blue in Exhibit 10)

has now jumped to 40%. In the Shinjuku submarket, the vacancy rate for

newly developed buildings skyrocketed to 89% in June 2010. Historically, the

vacancy rate for overall buildings has lagged the vacancy trend for newly

completed buildings. Based on this leading indicator, therefore, the overall

office vacancy in Tokyo is expected to increase a little further, to be followed

by a slow and gradual recovery starting in late 2010.

The vacancy rates in second tier cities have risen above 10%. In June 2010,

the office vacancy rate rose to 15.5% in Fukuoka, 13.4% in Nagoya, 12.1% in

Sapporo and 11.8% in Osaka. Although the increase in vacancy rates in

these regional cities is slowing down, demand is still weak in these markets

and the vacant space is not likely to be absorbed in the near future.

the office vacancy rate rose to 15.5% in Fukuoka, 13.4% in Nagoya, 12.1% in

Sapporo and 11.8% in Osaka. Although the increase in vacancy rates in

these regional cities is slowing down, demand is still weak in these markets

and the vacant space is not likely to be absorbed in the near future.

The recovery of sales at shopping centres and department stores has lagged

high streets. Sales at shopping centres in April and May 2010 (existing store

basis) fell 2.6% from the same period last year, but the speed of deterioration

has been slowing. Sales at department stores declined 2.9% while chain

stores declined 5.1% in the same period.

Nikkei RIM’s consumption forecasting indicator (CFI), a survey that predicts

future consumption trends six months in advance, also indicates recovery of

consumer confidence, recapturing 80 points for the first time since the

Lehman Brothers bankruptcy of 2008. Restrictions on visas for Chinese

tourists to Japan were eased in July 2010, and Japanese high street retailers

expect the number of Mainland Chinese shoppers to increase over the

coming months.

high streets. Sales at shopping centres in April and May 2010 (existing store

basis) fell 2.6% from the same period last year, but the speed of deterioration

has been slowing. Sales at department stores declined 2.9% while chain

stores declined 5.1% in the same period.

Nikkei RIM’s consumption forecasting indicator (CFI), a survey that predicts

future consumption trends six months in advance, also indicates recovery of

consumer confidence, recapturing 80 points for the first time since the

Lehman Brothers bankruptcy of 2008. Restrictions on visas for Chinese

tourists to Japan were eased in July 2010, and Japanese high street retailers

expect the number of Mainland Chinese shoppers to increase over the

coming months.

The capital value index of existing condos (i.e., the re-sale price index) hit bottom in August 2009. The price gradually recovered through March 2010,

but has since stabilised.

Residential rents, which have been relatively stable6, started to weaken in

February 2009 and have declined by 5.8% to date. Privately granting new

tenants a free-rent period for a month or two has become a popular incentive,

although it is not reflected in the statistics.

but has since stabilised.

Residential rents, which have been relatively stable6, started to weaken in

February 2009 and have declined by 5.8% to date. Privately granting new

tenants a free-rent period for a month or two has become a popular incentive,

although it is not reflected in the statistics.

Research Topic: Japan’s capital market in a global context

The Japanese capital market is the second largest in the world after the US,

and Japan is also home to the world’s largest pension fund. Yet even in the

global financial market, the scale of Japan’s capital resources frequently

escapes notice. In this analysis, we present an overview of Japan’s capital

market in a relative context. We compare the characteristics of the Japanese

capital market (especially the institutional market) and the funds domiciled in

Japan with global peers.

We begin with a comparison of national household financial assets (shown in

Exhibit 18 on a per capita basis). This exhibit shows how household financial

assets are allocated in selected major countries. Japan’s household financial

assets average US$129,000 on a per capita basis, ranking it second only to

the US as of the first quarter in 2010 (or year-end 2009 for European

countries).

Japan’s households allocate more than half (55%) of their financial assets to

cash and bank deposits (blue in Exhibit 18), reflecting the risk-adverse

character of the average Japanese household7. The Japanese government

has been trying to stimulate equity and mutual fund investment among retail

investors but any significant shift in household investment patterns now

seems to be on hold due to the latest financial crisis.

The Japanese capital market is the second largest in the world after the US,

and Japan is also home to the world’s largest pension fund. Yet even in the

global financial market, the scale of Japan’s capital resources frequently

escapes notice. In this analysis, we present an overview of Japan’s capital

market in a relative context. We compare the characteristics of the Japanese

capital market (especially the institutional market) and the funds domiciled in

Japan with global peers.

We begin with a comparison of national household financial assets (shown in

Exhibit 18 on a per capita basis). This exhibit shows how household financial

assets are allocated in selected major countries. Japan’s household financial

assets average US$129,000 on a per capita basis, ranking it second only to

the US as of the first quarter in 2010 (or year-end 2009 for European

countries).

Japan’s households allocate more than half (55%) of their financial assets to

cash and bank deposits (blue in Exhibit 18), reflecting the risk-adverse

character of the average Japanese household7. The Japanese government

has been trying to stimulate equity and mutual fund investment among retail

investors but any significant shift in household investment patterns now

seems to be on hold due to the latest financial crisis.

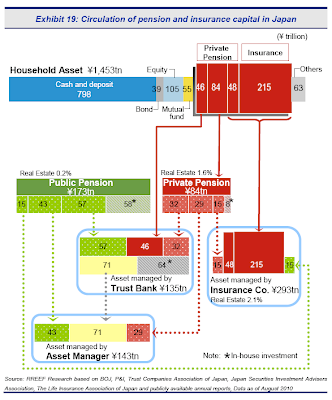

Exhibit 19 illustrates the circulation of pension and insurance capital in Japan

from initial investor all the way through to asset deployment. The chart traces

the scale of capital entering the market from original sources (i.e.,

households and public pensions), then follows this capital through a complex

path of pass-throughs and investment relationships to show which

institutional players ultimately deploy these assets. The aggregate asset size

held by households in Japan was JPY1,453 trillion (tn) as of the end of the

first quarter 2010, with 27% of that total held as life insurance or in private

pensions (red in Exhibit 19). This proportion (27%) is exactly the same as the

one shown in Exhibit 18 above.

This private pension money, together with public pension money, is either

7 This huge scale of household bank deposits underlies the current Japanese financial structure

which is characterised by a predominance of indirect financing by commercial banks.managed by trust banks (JPY135tn), by insurance companies (JPY293tn),

and/or by asset managers (JPY143tn) with some portion being managed inhouse

at each pension fund. Allocations to real estate are generally very low

in Japan, about 0.2% at public pensions, 1.6% at private pension funds, and

2.1% at major insurance companies respectively.

Since trust banks manage the largest portion of pension capital directly and

they have the closest relationships with pensions, they are regarded as ‘gate

keepers’ of pension funds in Japan, although more than half of their capital

(JPY 71tn) is being passed on to asset managers indirectly.

Below is the global ranking of large pension funds and sovereign wealth

funds (SWFs) by asset size. Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund

(GPIF) is by far the world’s largest fund with an asset size of well over one

trillion dollars, followed next by SWFs of natural resource-producing countries

such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Norway, and then by SWFs of Asian

countries8. Large pensions in Europe, the US, and Asia are ranked as well.

The following chart shows a comparison of portfolio allocations among major

pensions and sovereign funds, based on publicly available data. Again,

Japanese funds are weighted toward lower risk assets such as government

bonds while the allocations to alternative assets are limited, especially at

GPIF which has no guidelines for allocating to alternative assets. Japanese

private pensions allocate more capital to riskier assets than public funds, but

these private pensions are still relatively more conservative than their global

peers. As a result, returns tend to be low at Japanese funds. Leading global

pensions and sovereign funds have higher allocations to equity and

alternative assets and have generated higher returns than Japanese funds.

Exhibit 22 shows the largest real estate acquisitions by either pension funds

or sovereign wealth funds since 2009. Some funds which used to have

limited exposure to real estate have become active in the market, purchasing

trophy assets across the world. On the other hand, large Japanese pensions

are behind some Asian peers and still keep a low profile in the real estate

world.

Based on our analysis and peer review of national capital markets, we draw

the following conclusions from this edition of ‘Research Topic’ about the key

market players in Japan. First, Japanese households are exceedingly risk

averse and show a strong preference to allocate financial assets to cash

rather than capital market products such as equity or mutual funds. These

preferences may eventually change, but a significant cultural shift is unlikely

to happen soon. While retail investment in the equity and mutual fund

markets still has potential to grow in Japan, the momentum is currently on

hold because of the latest financial crisis.

Second, Japanese institutional investors in general have characteristics

similar to households such as limited exposure to riskier assets. The

Japanese GPIF, for example, has minimal exposure to alternative assets, but

Japanese private pensions allocate more capital to riskier assets.

Nevertheless, Japan’s private pensions still lag their global peers in portfolio

diversification. In fact, Japanese pensions are behind not only western funds,

from initial investor all the way through to asset deployment. The chart traces

the scale of capital entering the market from original sources (i.e.,

households and public pensions), then follows this capital through a complex

path of pass-throughs and investment relationships to show which

institutional players ultimately deploy these assets. The aggregate asset size

held by households in Japan was JPY1,453 trillion (tn) as of the end of the

first quarter 2010, with 27% of that total held as life insurance or in private

pensions (red in Exhibit 19). This proportion (27%) is exactly the same as the

one shown in Exhibit 18 above.

This private pension money, together with public pension money, is either

7 This huge scale of household bank deposits underlies the current Japanese financial structure

which is characterised by a predominance of indirect financing by commercial banks.managed by trust banks (JPY135tn), by insurance companies (JPY293tn),

and/or by asset managers (JPY143tn) with some portion being managed inhouse

at each pension fund. Allocations to real estate are generally very low

in Japan, about 0.2% at public pensions, 1.6% at private pension funds, and

2.1% at major insurance companies respectively.

Since trust banks manage the largest portion of pension capital directly and

they have the closest relationships with pensions, they are regarded as ‘gate

keepers’ of pension funds in Japan, although more than half of their capital

(JPY 71tn) is being passed on to asset managers indirectly.

Below is the global ranking of large pension funds and sovereign wealth

funds (SWFs) by asset size. Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund

(GPIF) is by far the world’s largest fund with an asset size of well over one

trillion dollars, followed next by SWFs of natural resource-producing countries

such as the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Norway, and then by SWFs of Asian

countries8. Large pensions in Europe, the US, and Asia are ranked as well.

The following chart shows a comparison of portfolio allocations among major

pensions and sovereign funds, based on publicly available data. Again,

Japanese funds are weighted toward lower risk assets such as government

bonds while the allocations to alternative assets are limited, especially at

GPIF which has no guidelines for allocating to alternative assets. Japanese

private pensions allocate more capital to riskier assets than public funds, but

these private pensions are still relatively more conservative than their global

peers. As a result, returns tend to be low at Japanese funds. Leading global

pensions and sovereign funds have higher allocations to equity and

alternative assets and have generated higher returns than Japanese funds.

Exhibit 22 shows the largest real estate acquisitions by either pension funds

or sovereign wealth funds since 2009. Some funds which used to have

limited exposure to real estate have become active in the market, purchasing

trophy assets across the world. On the other hand, large Japanese pensions

are behind some Asian peers and still keep a low profile in the real estate

world.

Based on our analysis and peer review of national capital markets, we draw

the following conclusions from this edition of ‘Research Topic’ about the key

market players in Japan. First, Japanese households are exceedingly risk

averse and show a strong preference to allocate financial assets to cash

rather than capital market products such as equity or mutual funds. These

preferences may eventually change, but a significant cultural shift is unlikely

to happen soon. While retail investment in the equity and mutual fund

markets still has potential to grow in Japan, the momentum is currently on

hold because of the latest financial crisis.

Second, Japanese institutional investors in general have characteristics

similar to households such as limited exposure to riskier assets. The

Japanese GPIF, for example, has minimal exposure to alternative assets, but

Japanese private pensions allocate more capital to riskier assets.

Nevertheless, Japan’s private pensions still lag their global peers in portfolio

diversification. In fact, Japanese pensions are behind not only western funds,

but also some Asian rivals, in diversifying allocations to alternative assets.

Because of their limited exposure to higher risk assets, the long-term return

of Japanese funds tends to be lower than the comparable returns of global

peers.

Finally, we recommend that this quarter’s ‘Research Topic’ be read along

with the previous edition (Japan Real Estate First Quarter 2010) which

focused on portfolio optimisation in April 2010. In the previous edition of

‘Research Topic’ we pointed out that based on modern portfolio theory

Japanese pensions in general should increase real estate allocations in their

portfolios in order to maximise their potential across the risk-return spectrum.By:Koichiro Obu &Orie Endo

No comments:

Post a Comment